Books for the Preservation of Knowledge of Humanity

By Wendy Spacek

Collection Management with a Preservation Perspective

In the fall of 2018 I joined the Preservation Lab as a Student Conservation Assistant. I was excited to engage my skills as a painter, printmaker, and DIY bookmaker to help preserve library materials. At the time, I was in the final year of my MFA in poetry and intended to continue at IU to complete my library degree. I started as most Student Conservation Assistants in the book conservation lab have: removing the staples from music scores and sewing them into pamphlet binders. To some it would seem a tedious job, but I found the meditative, repetitive task relaxing and I was eager to learn more.

For the next year and a half I learned treatments and tricks from everyone who worked in the lab, picking up details about how books are made, why they fall apart, and how books are identified and prioritized for repair or stabilization. By early spring of 2020, I was practicing just about every treatment available to Student Conservation Assistants in the lab. Then suddenly, like many others, everything changed because of COVID and I was no longer able to work in the lab.

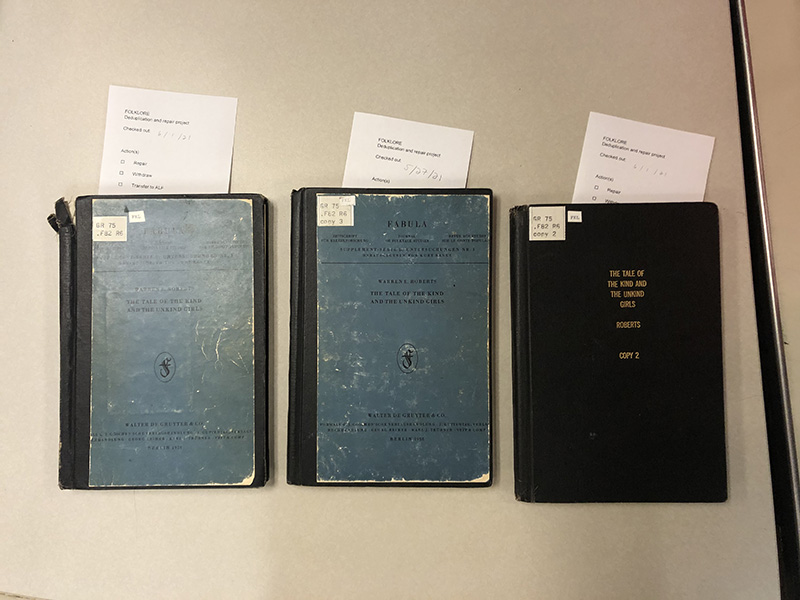

Over the year of quarantine and lock-down that followed, I continued my MLS coursework remotely, leaning into my interests in collection management, research support, and teaching. When vaccinations became widely available in the spring of 2021, I was delighted to be offered the opportunity to return to the lab for the summer to participate in a de-duplication and preservation project for the Folklore Collection; a project designed as a pilot for larger de-duplication and preservation efforts. Working on this project both mobilized and tested my existing preservation knowledge, expanded on my database management skills, and deepened my understanding of library workflows, policies, and procedures.

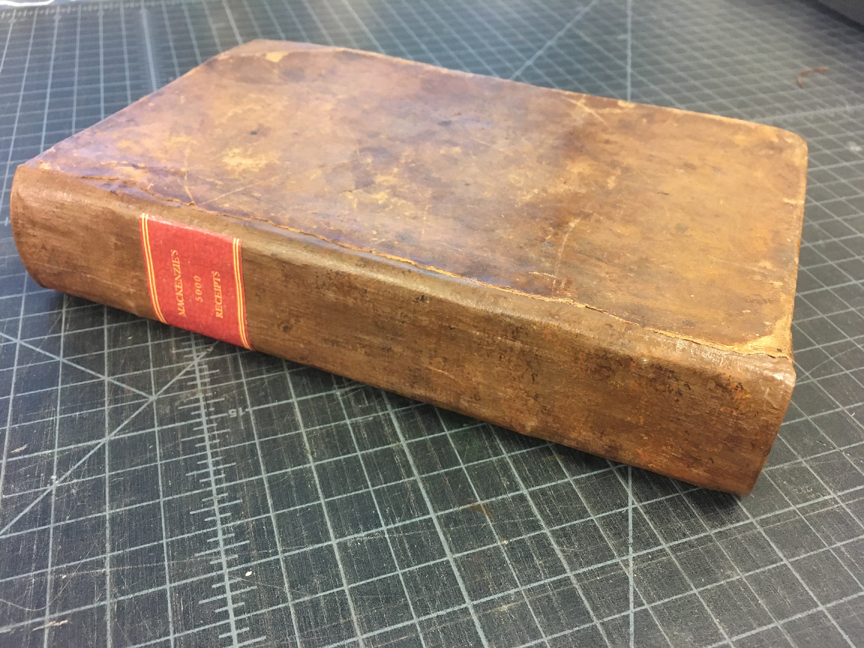

For the next month and a half, hundreds of books passed through my hands. It was my role to look at each set and evaluate them based on how they were made, evaluate prior repairs, and their present condition (see the previous blog on this site, You Can't Judge a Book by the Cover, which explains a lot of the thinking that goes into such an evaluation).

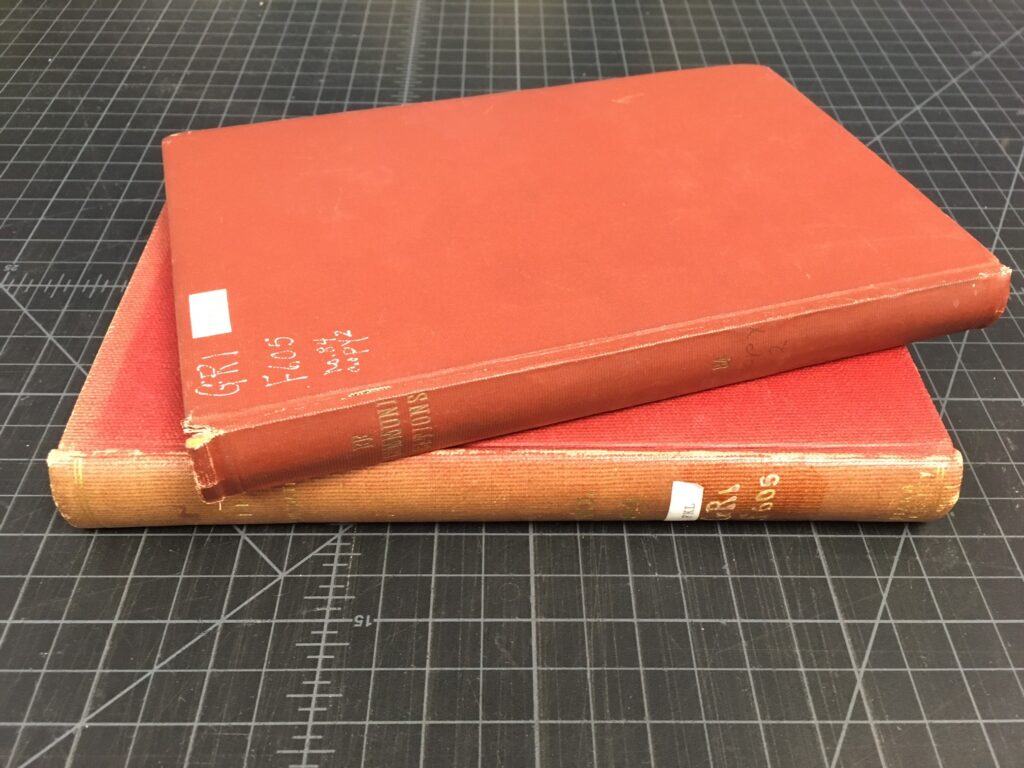

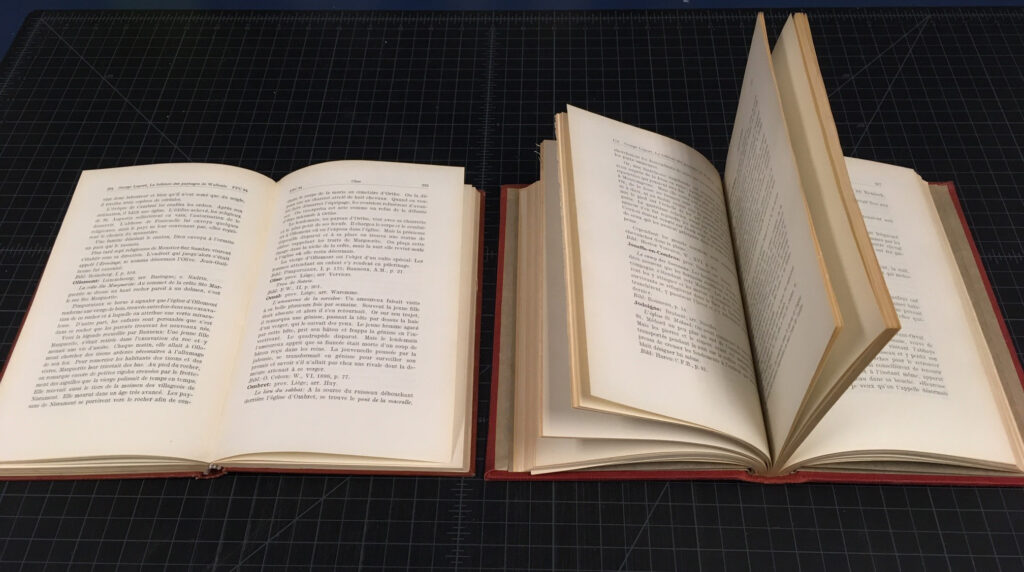

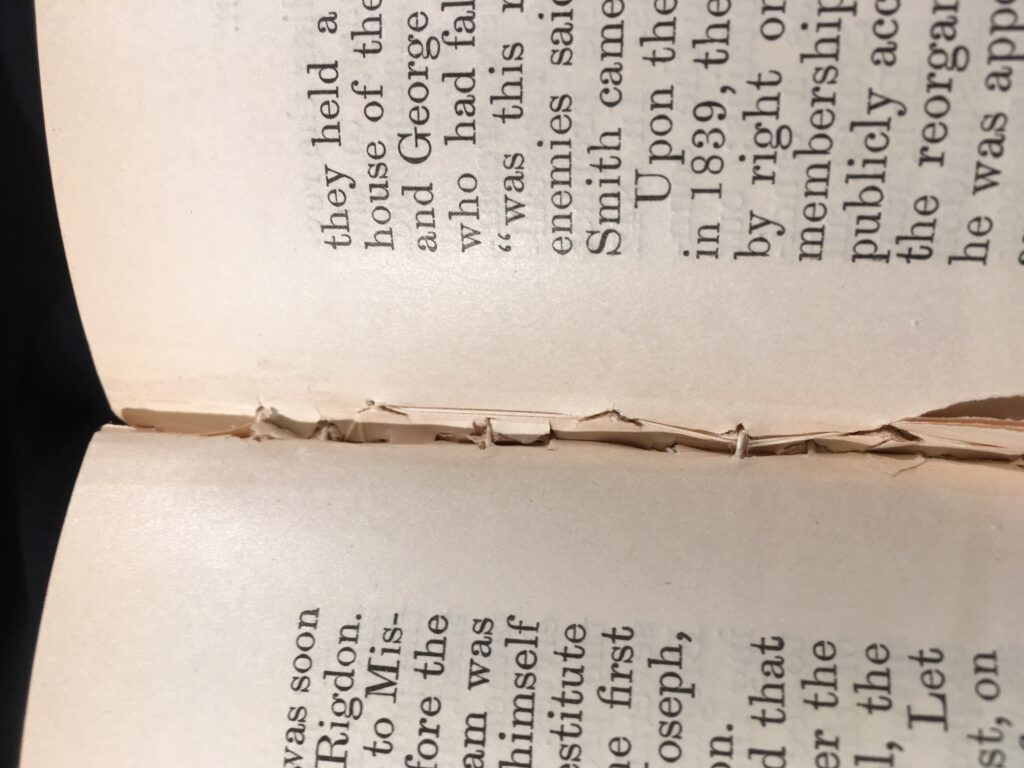

Some sets were easy: a copy sewn through the fold with little wear to the interior or covers was an obvious choice when compared to an over-sewn copy with too-tight binding, and brittle, torn pages.

When these decisions became difficult was when choosing between very bad copies of the same book.

This is where the skills I'd gained in my years as a Student Conservation Assistant really came in handy. Because of my past preservation experience, I could estimate how much time it would take to complete various repairs, identify opportunities for simpler, less-time consuming fixes, or know when to bring the two awful copies to my supervisor for her opinion.

As I worked my way through the project, giving recommendations for repair and turning the books over to the full-time conservation staff, I encountered binding methods I'd not yet seen, books with unidentified substances smeared across their pages, heart-warming inscriptions to beloved professors, and the unfortunate reality of acidic paper gone brittle and crumbling as I turned each page. Through conversations with the conservation staff, I expanded my knowledge of preservation techniques and witnessed how conservators make different decisions based on the item and its needs. There are a number of ways to approach a book in need of repair, and sometimes two conservators will make different decisions, or the same conservator might take a different approach on a different day, due to external factors like overall workload or the skill level of available staff. Like so many things in the library world, there is more than one way to do it! Hearing back from full-time preservation staff about how the treatment they ultimately performed aligned and differed from my recommendation was uniquely instructive, and served to deepen knowledge of book repair techniques and decision-making.

While I worked on the project, I evaluated the condition of over 1000 individual monographs. Beyond the preservation skills I expanded upon, I also deepened my knowledge of library management software, database software, and library workflows and procedures. While evaluating titles I uncovered and flagged numerous cataloging errors, a happy side effect of such a project. Between pulling books in the stacks at Wells, packing totes of books and organizing them on carts, and comparing copies and making recommendations, I read up on preservation management in libraries, and even had some time to make some conservation treatments of my own by mending torn pages with Japanese paper and wheat paste.

This project is a wonderful example of preservation staff and subject librarians working together to maintain the health and continuation of a collection. As I move into my new position as the Arts & Humanities Librarian at Central Washington University I'll bring with me a theory of collection management that integrates principles of preservation and emphasizes cooperative relationships between public and technical library services, centering responsible stewardship of library resources with the shared goal of ensuring continued access to research collections for decades to come.

Part One

You can't judge an apple by looking at a tree

You can't judge honey by looking at the bee

You can't judge a daughter by looking at the mother

You can't judge a book by looking at the cover.

— Bo Diddley / written by Willie Dixon

Are you looking for reading recommendations?

or maybe a Bo Diddley recording?

If so, you are probably in the wrong place.

On the other hand, if you have books you want to keep for a long time, and perhaps pass on to your children, you may find this useful. Ditto if you work in a research library. Ditto if you've ever wondered how books are put together. We are talking here about things that affect a book's chances of long-term survival.

For out of old fields, as men say,

Comes all this new corn from year to year;

And out of old books, in good faith,

Comes all this new science that men hear.

— Geoffrey Chaucer, Parlament of Foules

Book conservators know how books are made, and importantly, why and how they fall apart. So I'm going to share some secrets about how to distinguish between a book that is likely to last and one that may not. Hint: As the title of this post suggests, one with a worn cover could very well be a better choice than one that looks good from the outside. In truth, the choice is not usually clear-cut — not by a long stretch. Nevertheless, better choices can be made, and made more easily, when armed with information about the physical aspects of books and how they are put together.

Book conservators work hard to keep books in good condition so that they will be there when you need them. But do you know what has helped the survival of our collective intellectual record more than the collective efforts of book conservators?

Lots. Of. Copies.

Any particular book or journal is likely to be found on the shelves of many libraries. Everybody knows that, and that is a good thing. And an individual library very likely has duplicates even within its own collection.

Redundancy is good in the world of information preservation, whether it is physical books or backups of your computer files. When bad things happen to good books — as they do — there will still be other copies.

So why worry about better or worse copies when we have lots of them?

Well, in recent decades the cost of maintaining vast print collections has become a pressing problem for libraries. The space devoted to books diminishes a library's capacity for other things, such as study space for patrons. When libraries run out of space, difficult choices often have to be made.

Since the 1950s, when post-war prosperity led to increasing rates of collection growth, libraries have used many strategies to cope. Microforms reduced the footprint of voluminous materials such as newspapers. Compact shelving was added. Interlibrary lending meant a library did not have to acquire every book. When those measures were no longer enough, high-density storage facilities were built to house books by size on 30-foot-high shelving. But today many libraries have filled up these facilities too, and financial support for yet more space has been hard to come by.

So what now?

You see where I'm going here. Shedding some of the copies would seem like a reasonable next step, especially older materials, which are no longer used as much as they once were. So this is indeed what many libraries are up to these days — withdrawing some copies, either within their own collections or in collaboration with other libraries.

Behold, the fool saith, 'Put not all thine eggs in the one basket' – which is but a manner of saying, 'Scatter your money and your attention ; ' but the wise man saith, 'Put all your eggs in the one basket and – WATCH THAT BASKET.'

– Pudd'nhead Wilson's Calendar. — Samuel Clemens/Mark Twain.

So then, how does one decide which are the best copies to keep? This is where knowing how books are made comes in.

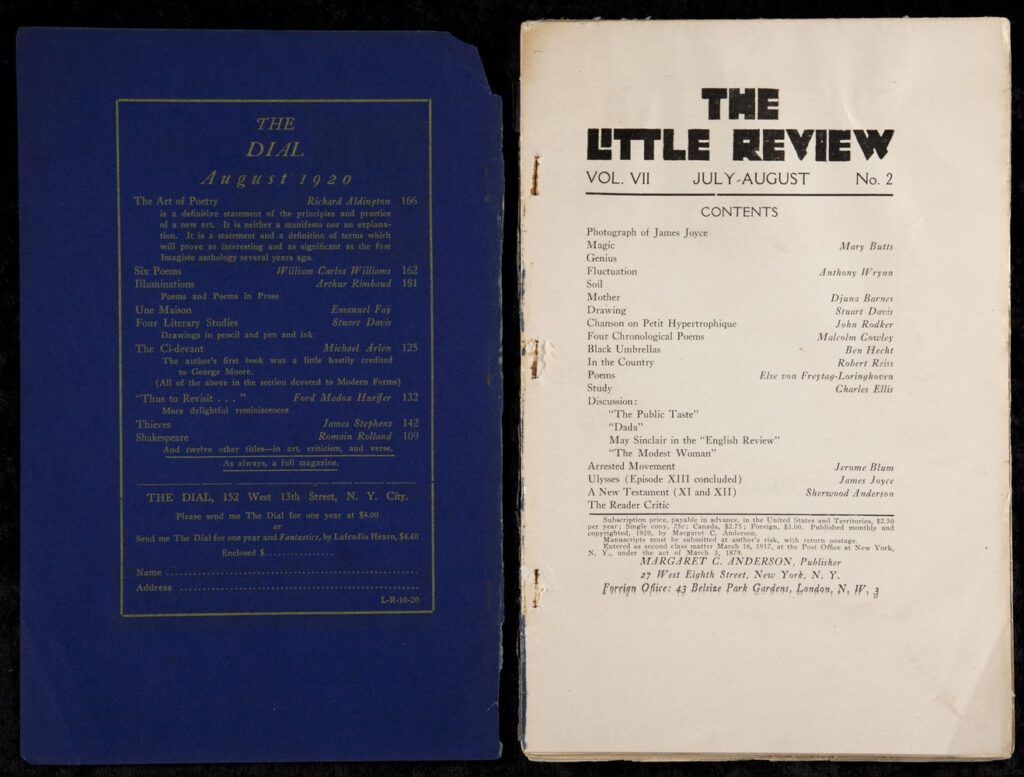

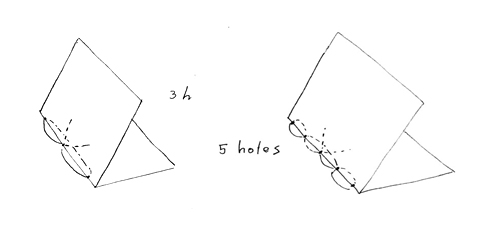

In Part Two, I'll get all technical and talk about how you can distinguish between a book that is likely to last and one that may not based on its construction. For now, I will pause and leave you to ponder this illustration. We'll come back to it.

You Can't Judge a Book by the Cover

Part Two

In Part One I suggested that looks can be deceiving to the untrained eye when it comes to judging which copy of a book has better odds of long-term survival. And I promised to share what book conservators know about how books are made, and how and why they fall apart. So now we are going to look under the hood (the covers, that is).

First, we have to talk about paper.

Way back when, before the Industrial Revolution, paper didn't grow on trees. It was made out of fibers from cotton and linen clothing and other rags.

But the increased demand for paper in the nineteenth century led to rag shortages, so in the 1840s papermakers began switching to wood pulp. Unfortunately wood-pulp paper becomes acidic, weak, and brittle over time, whereas older paper made from cotton or linen fibers has remained strong and flexible for centuries. By the 1980s, with the problem now quite evident in library stacks, papermakers began converting to making acid-free paper. But between the 1840s and the 1980s millions of books were produced. And libraries have lots and lots and lots of them.

So the condition of the paper is a big factor for long-term survival.

But now you are thinking that books published at the same time are likely to have the same kind of paper, right? And you would be correct. So this doesn't help a lot by itself when comparing copies. But it is often a combination of factors , including paper strength, that leads to a book's demise.

Binding

An essential thing that makes a book a book is that the pages are joined, or bound, together along one edge in some way. There are numerous ways this can be done. And the way a book is bound often does vary from one copy to the next. The main reason for this is that older books in libraries are likely to have been rebound at some point. And some of the rebinding methods used in the past were, shall we say, better than others. Also, wear and tear often varies from one copy to the next.

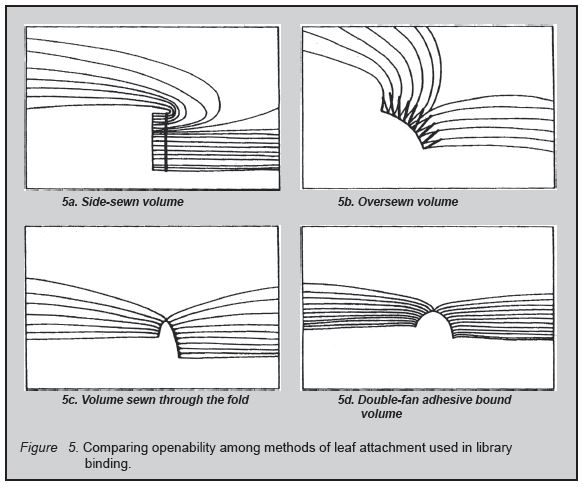

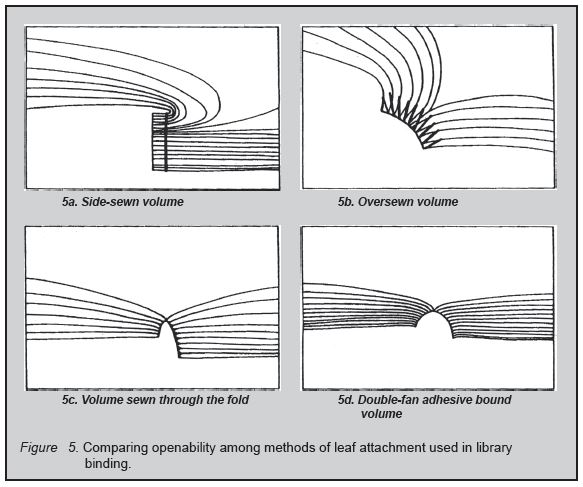

Openability

A simple but important feature to look for is openability — whether a book lies open on the table by itself, or if you have to hold it open. The way the pages are joined together largely dictates this. Openability is important, not only because those that don't open well are less convenient to use — although they are — but because a restricted opening is one sign of a binding method that makes future repairs difficult or impossible. (Sometimes the thickness of the paper, or the direction of the paper grain also come into play.)

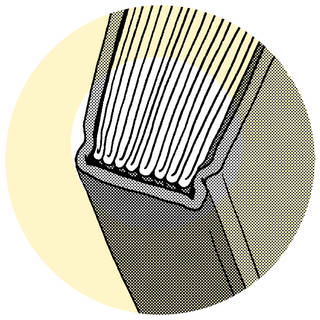

The openability of the most common binding, or "leaf attachment," methods found in library collections are illustrated below. Restrictive bindings — those that do not open easily — put stress on the pages. Books that open easily allow the pages to move freely. A book with brittle paper and poor openability is likely to end up broken and sad. And difficult to save. But when a book is bound in a flexible manner, there's hope, and the chances are better that it can be repaired.

Identifying Leaf Attachment Methods

Below are descriptions of the leaf attachment methods most prevalent in library collections, along with illustrations to help you know what to look for to tell one from another.

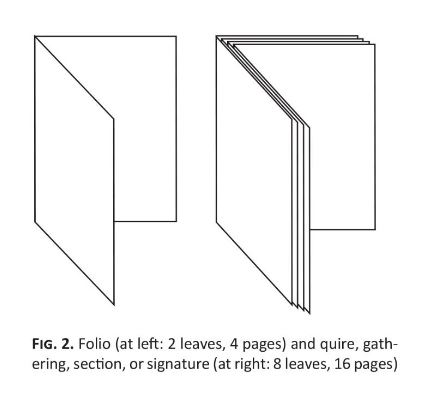

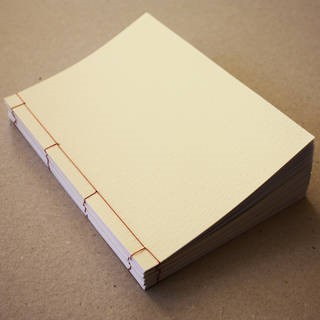

Sewing Through the Fold (5c above) is a traditional method of joining the leaves of a book together to form a text block, and has been in use since as early as the 2nd century AD. So it's kind of time tested.

Sheets of paper (folios) are folded together in groups (called signatures, sections, gatherings, or quires).

and the groups are sewn one to the next with needle and thread.

Sewing through the folds is still the way that lots of books are made. Attaching the pages together through the folds makes a book that opens well, is flexible, and allows for future repairs. There is not a lot of stress on the pages, and that is helpful if and when the paper becomes brittle and weak.

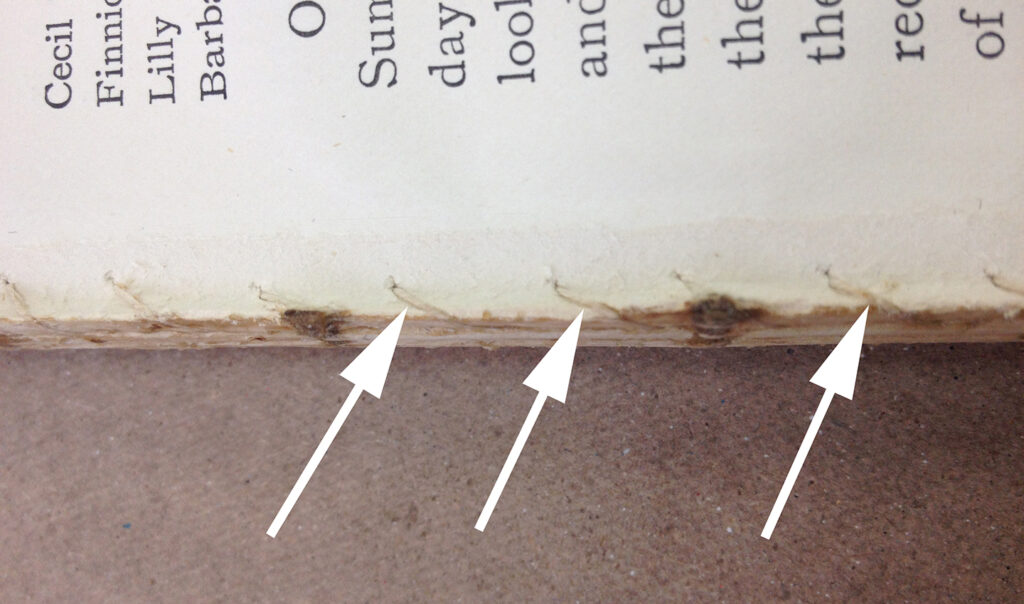

Sewing through the folds can be found in paperbacks as well as hardcovers. Look for even stitches in the center folds and a scallop pattern at the top or bottom edge of the book.

Adhesive binding (5d) joins single leaves (rather than folded sheets) together with glue and results in good openability, because the pages are attached only by their very, very edges. As long as there are adequate margins, adhesive bindings usually can be rebound.

Burst binding is a variation of adhesive binding, but it's a tricky one. They can be confusing to distinguish from a book sewn through the folds. The top edge has the scalloped edge like a book in signatures sewn through the fold. That is because it is in signatures. It's just that instead of the signatures being sewn, slots are cut through the folds and adhesive is forced (or burst) through to hold the signatures together. When you look closely at a burst binding you will not see any threads. These usually can be rebound adhesively after cutting off the folds.

Most mass market paperbacks are made with poor-quality adhesives that dry up and cause pages to fall out or the text block to split, as shown below. But if the inner margin is wide enough, these can usually be rebound with a better adhesive, as only a tiny amount of the page edges need to be trimmed away.

Double-fan adhesive binding, which uses a high-quality, long-lasting adhesive, is done by commercial library binders and in book conservation labs. The pages are clamped in a press, fanned out, and adhesive is applied. Then the pages are fanned the other way and more adhesive is applied. This deposits adhesive on both sides of the pages (1/16 inch or less). This type of adhesive binding holds up well in most books, but does not work as well on books with thick, stiff pages.

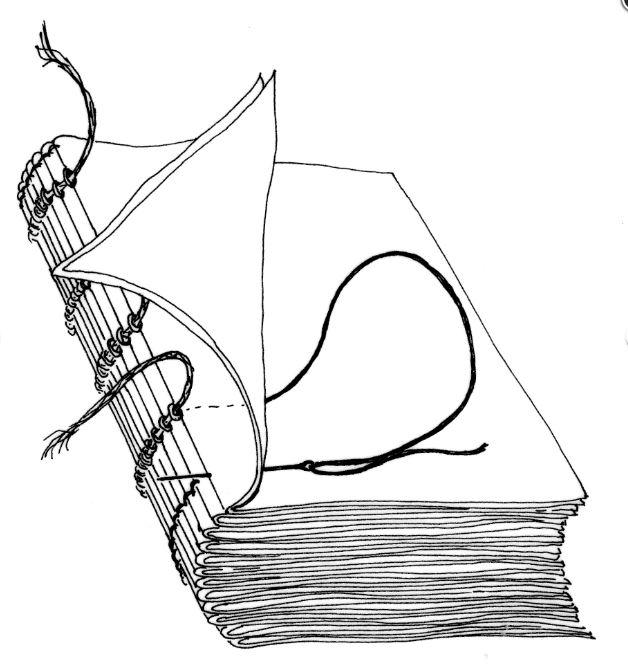

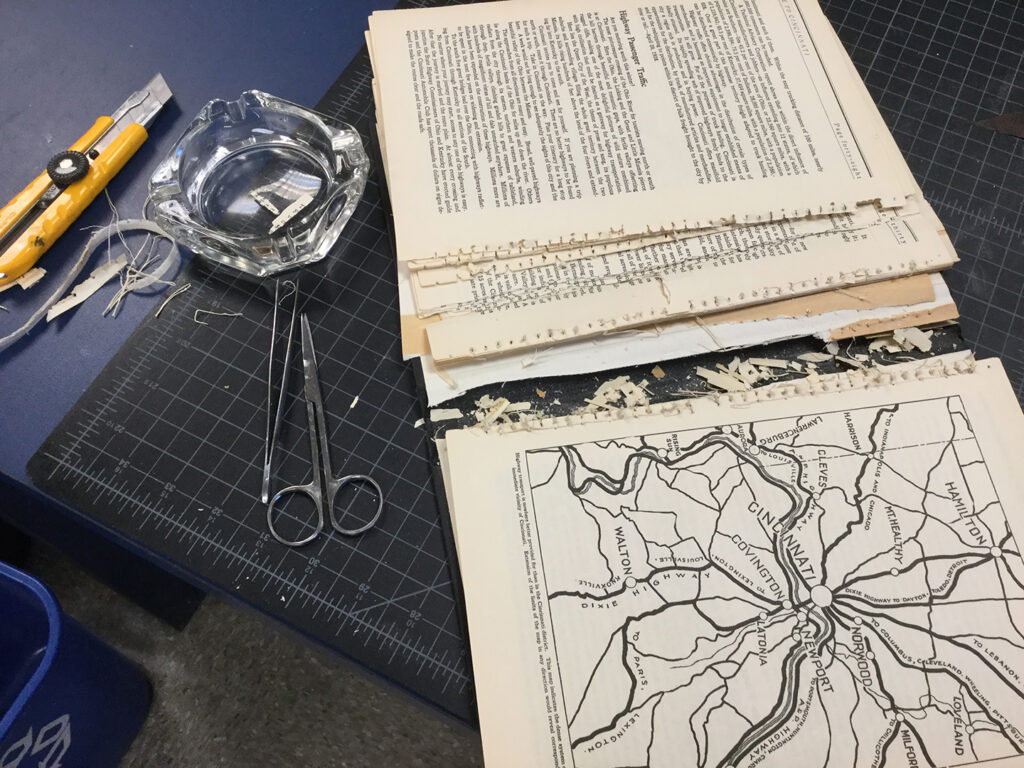

Oversewing (5b), the most restrictive leaf attachment method, was used liberally until about 1985 by commercial library binders. Many books that were sewn through the folds originally were rebound later by oversewing, which requires chopping off the folds and some of the inner margin to make a stack of single sheets. Oversewing was also used to bind together the issues that make up journal volumes. Since the mid-1980s, oversewing has largely been replaced by double-fan adhesive binding.

To oversew a book, the folds are chopped off (if present) and a few pages are put into an industrial machine that has a row of threaded needles. The needles and threads pierce through the page edges many, many times. Then another clump of pages is added, and the machine sews through them and interlocks the stitching with the one before.

An oversewn book with flexible paper is probably going to last a long time, but if the paper is brittle, there will be a lot of page breakage, and you may not be able to put Humpty Dumpty together again.

Below is an oversewn book taken apart, page by page, snip by snip with fine scissors and tweezers. There is so much strong thread that it can take hours to take apart one volume. The resulting pages look similar to those torn out of a spiral-bound notebook.

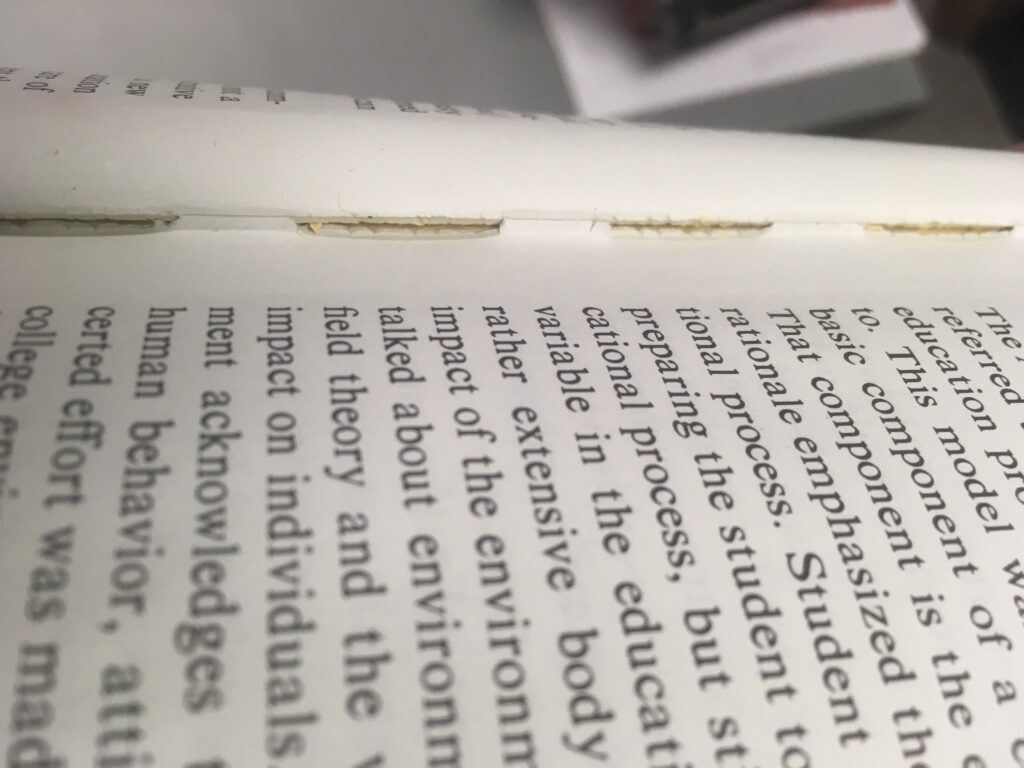

Besides the restricted opening, another way to tell that a book is oversewn without taking it apart is to look for the close, irregular stitches in the inner margin. This is often visible in older books as they start to weaken.

Also, almost all oversewn books have plain buckram cloth covers.

Because oversewn books are made up of single sheets, rather than folded signatures, you won't see a scallop pattern at the top or bottom as you do with books sewn through the folds.

Hand-oversewn books are less common, but sometimes repairs were done by a kind of oversewing. The most likely hand oversewing you would encounter is at the front of a book (where damage most often occurs first). Hand oversewing is also called whip stitching or overcasting. This type of oversewing restricts opening, but is not as damaging as machine oversewing because the folds are usually retained, there are not nearly as many stitches, and the stitches are much easier to remove.

Side sewing (5a) is another restrictive binding method. It can be sewn by machine or by hand. All the pages are sewn in one long row of even stitches. The stitches can be removed, allowing for rebinding. This can be a bit time consuming, but it can be done.

Japanese stab-sewn books are usually made with thin flexible paper and adequate inner margins.

Side stapled books are similarly restricted in opening, but they are usually easier to take apart to repair or rebind. Side sewing and side stapling are usually done on thin books or pamphlets made up of single sheets of paper, but sometimes books made from folded pages have been side sewn or stapled.

Pamphlet binding is a single signature of pages sewn together through the fold, often together with a simple cover. Like a book with multiple signatures sewn through the folds, this is a flexible leaf attachment method that can be repaired or rebound very easily. Pamphlets, musical scores, popular journals, ephemera and other short works are often made up of a single signature stapled through the center. Staples can be replaced by sewing to improve durability.

So, yes, it's complicated, but at least now you know – you can't judge a book by the cover.

For more information on book structures not covered here, see:

University of Illinois. Preservation Self-Assessment Program. Collection ID Guide. Book and Paper, Binding Types

and for an excellent analysis of the many factors involved in withdrawing copies, see:

Considering Sameness of Monographic Holdings in Shared Print Retention Decisions.

Lately, there are more and more opportunities to attend virtual events, lectures, webinars and presentations on the subjects of preservation and conservation of heritage collections. An upcoming event is a case in point: members of staff from University Archives, the Preservation Lab, and Advancement have put together an entertaining evening: "IU Baseball in Japan, 1922: A Trip We Can All Take!" to be held September 22 from 5:00-6:30pm EST. Paper Conservator Doug Sanders will elaborate on the conservation work needed for a scrapbook and silk banner associated with the historic 1922 trip.

For more information and registration (free, yet required) please see the following listing: https://events.iu.edu/libraries/view/event/date/20200922/event_id/137688

Image # P0042248 Archives Photograph Collection, Indiana University

A la Recherche du Temps Perdu | In Search of Lost Time

And we're back …

Well actually, some of us never left. A skeleton crew has been working in the IU libraries throughout the pandemic, just to keep the pipes clear so that information continues to flow for you, dear readers. Meanwhile, the rest of us were hunkered down for almost 4 months in our kitchens, dining rooms, bedrooms, and back porches, and yes, sometimes even in our parked cars in the IU Stadium lot in order to get an Internet signal. With eyes and fingers glued to our computers, we have been doing all the things a modern library can do online — placing orders for e-books, paying for them, reference services, cataloging, and so many other things you never even knew went on behind the scenes in a library.

As we prepare for Fall 2020, additional staff are back on campus, mainly those who work with the physical collections – the books, journals, and other things you can hold in your hands and sometimes even take home. Some staff re-shelve books, some repair them, some put the call numbers on them, some prepare them for deposit in our state-of-the-art collection storage facility.

We are following IU's guidelines to keep you and ourselves safe. One concern unique to a library, but not addressed by the campus guidelines, is the handling of those physical collections we talked about. You may get up close and personal with the books you read, and when you return them, staff need to handle them — to get them checked back into the circulation system, possibly repair them, and re-shelve them. In ordinary times, that is.

So we thought you might want to know what we are doing about that.

Although we know that disinfectants are effective in killing the virus that causes COVID-19, unfortunately we also know they can damage library materials. Not to mention how long it would take to disinfect all the pages of a pandemic-appropriate book such as Marcel Proust's A la Recherché du Temps Perdu. And please — don't even think about microwaving books; nothing good can come of that.

But there is a simple solution (no, not that kind of solution). We just quarantine the books coming back to the library, because we know that the virus has a finite period of viability. Although we are still learning about SARS-CoV-2 transmission, recent studies to address library concerns found that the virus is no longer detectable on library materials after three days. The REALM project is ongoing, so check there if you are interested in what they are doing.

While the library buildings remain closed to the public, you can submit requests online to borrow books, and schedule a no-contact pickup appointment. Please know that any library materials you borrow will have been quarantined for three days after someone else has used them. And the staff preparing those materials for you are washing their hands, disinfecting surfaces, wearing face coverings, and keep six feet from others.

Beyond the physical collections, there are ten tons of books you can read online in HathiTrust, and lots of other e-books are available by searching IUCAT. Find up-to-date information on the current library services page about borrowing, research help, requesting articles, access to lots of online resources, and other services.

So please wear a face covering, wash your hands, and while you're at it, maybe read a book?

Continue reading more from the Preservation Lab blog to find out about some of the ways we keep the collections in good condition so that they are there when you need them. Also find out how we have been managing through the pandemic, including this totally apolitical analysis of the meaning of a word – depending on your (book) world view. It is light-hearted fun, but also illuminating.

Stay safe out there.

Now that we are gearing up to get back into the lab in the next couple of weeks, I can share something I have been thinking about while working from home.

What do you think of when you hear the word "bookworm"?

Is it this?

Or this?

Or this?

Chances are, your answer will vary greatly depending on what part of bookworld you live in. Children's librarians probably think of something like the first two. Those of us on the preservation and conservation side of things, probably think more about the third.

Just for fun, let's spend a moment analyzing these images. First, I will need you to do a quick Google search for "bookworm" and let's just look for a moment at these worms.

Clearly, from these images, there are a number of things which we must understand about bookworms.

• 99% of Bookworms are green

• 95% of bookworms wear glasses

o Corollary: the glasses must have round lenses

o Corollary: the frames must be black or red

• The bookworm really should be depicted holding a book, but occasionally may be depicted in a more realistic burrowing through the book fashion. (we'll get there)

o Corollary: the book must have a red cover.

If I may have a pedantic moment here, I actually judge most of these "worms" to be caterpillars. I base this solely on the fact that caterpillars are more likely to have something resembling hands which which to grasp a book.

Alternatively, the image search may turn up something like this:

This version allows for slightly more variation. However, a few rules do apply:

• Over 80% of human bookworms are female

• Most human bookworms wear glasses

• Corollary: frames must be plastic or horn rims.

• Dang it, those are my glasses.

THE ENTOMOLOGY

Here's the basics:

• Bookworms are real things

• They aren't really worms

Actual book eaters come in a large number of forms and can do a huge amount of damage to collections.

Here is an abbreviated list of the critters in question:

1. Book lice.

Not lice in the way we generally consider lice. They are not parasitic, meaning that they do not feed on live hosts. However, they do consume old binding adhesives, paper, wood and leather. They also seem to be attracted to molds which inhabit old books.

As an aside – molds are living organisms, so I guess book lice are parasitic on molds? Is it considered parasitism if the living organism is only part of a varied diet? Also, often old colonies of molds in books are actually dormant (if not totally dead). This is a thing which we often have to consider when treating moldy items in the lab.

2. Beetles.

Let's discuss beetles for a moment. There are at least a quarter of a million species of beetles on Earth. Many are beneficial to humans. They act as predators of plant pests (such as aphids), as essential pollinators , and as a human food source. Some species in adult, or more commonly, larval form feed on books. Most prefer old binding adhesives and paper, but some go for leather bindings.

3. Termites.

This is serious people. Not only will termites eat your books, they will also eat your bookshelves.

4. Moths.

In larval form, they will eat your sweater, they will eat the quilt your grandmother made for you. They will also eat cloth book bindings.

5. Silverfish.

Just ugh. I'm pretty insect tolerant, but these things creep me out. We have to consider them, however, because paper is their meal of choice when they live in libraries. They may also have been an insect that Robert Hooke identified as a bookworm in his early microscope work in the 1600s.

6. Cockroaches.

The less said the better. Sorry cockroachologists.

And let's take just a moment to celebrate a fierce looking critter which eats books eaters. Friends, I introduce to you, the pseudoscorpion.

It is a tiny arachnid which feeds on book lice, moth and beetle larvae, ants, and other insects. Because of their very small size (about 2 – 8 mm) they are often not noticed by humans, or are taken for small spiders.

THE DAMAGE

The lacy effect can be pretty and all, and may have predated modern, human book carving techniques, but it's not so great if you want to retain the information in those pages.

One of the classic treatments of the insect bookworm is in William Blades' The Enemies of Books, first published in 1880. Blades was a printer and bibliophile who did research into early British printing, and thought a lot about old books. His book is readily available online and I highly recommend reading it over. But then, like Blades, I am also a bit of a curmudgeon who thinks that the whole world is out to destroy books. Given my profession, the chapter on the evils of bookbinders does make me squirm. Here is a brief quote from his chapter on bookworms:

"Anathemas have been hurled against this pest in nearly every European language, old and new, and classical scholars of bye-gone centuries have thrown their spondees and dactyls at him…But as a portrait commonly precedes a biography, the curious reader may wish to be told what is this "Bestia audax", who so greatly ruffles the tempers of our eclectics, is like. Here, at starting, is a serious chameleon-like difficulty, for the bookworm offers to us, if we are guided by their works, as many varieties of size and shape as there are beholders."

Later in the chapter, he goes on to describe in an astonishing amount of detail, a bookworm "race" through a volume from the 1400s, tracking each worm trail through the thickness of the book until its creator perished. (Or maybe just turned around?)

Just a note: as a profound lover of books as physical objects, I can only imagine that e-readers would have made poor Mister Blades apoplectic.

I'm not going to go into methods of treatment for insect damage to collections, or for pest eradication. There are many, many far more informed folks out there who have published complete and detailed information. I will shout out Mary Lou Florian, whose book Heritage Eaters is a great resource. The Northeast Document Conservation Center also has a wealth of information.

Modern libraries often have better climate control than in previous generations, and this would lead to fewer infestations than in the past. But they are by no means unheard of. For example, when libraries and museums accept donations of old collections kept in poor storage conditions, the possibility of insect or mold infestations must be considered before materials are accessioned.

THE ETYMOLOGY

Really, all the above is all just so many diversions from what I was originally interested in writing about. I wanted to see if I could track down the moment in history when the bookworm went from being a literal book eater to a metaphor for a human who reads all the time and wears glasses and is socially awkward.

And this is what I found, folks.

First: The shift happened a lot earlier than I expected.

Two: IT WENT THE OTHER DIRECTION!

Yep, I was incredibly surprised to find out that the Oxford English Dictionary (can we please get a round of applause for the generations of fine folks at the OED) indicates that the term "bookworm" was first used in 1580 to describe a person who spent too much time reading. And doing other things which aren't such a great idea:

1580: E. Spenser & G. Harvey, Three Proper & Wittie Lett.:

"A morning bookeworm, an afternoone maltworm."

1601: B. Jonson, Fountaine of Selfe-love:

"Peruerted, and spoyld, by a whoore-sonne Book-worme, a Candle-waster"

And really, right now while I have been spending so very much time at home, being a bookworm, a maltworm and a candle waster seems like a pretty good idea.

It wasn't until 1654 that someone described a non-human bookworm:

1654 R. Whitlock Ζωοτομία

"Book-worme is of all Creatures the longest lived."

Sorry, Ming the 500 year old clam. That 110 day-old book louse has got you beat.

All of these descriptions of bookworms were pejorative. Worms of all forms were thought to be basically disgusting and harmful. Or maybe they were actually dragons? Early English folklore sometimes uses the words "dragon" and "worm" interchangeably. The bookish reference to a human worm predates the insectoid version, because "worm" was a common Elizabethan insult. Then later, as we get into the taxonomy of the book eating insects, since the term already exists, it is applied in that context as well. Plus, sometimes the book eaters are larvae, which look like worms.

So who was the tricksy librarian or teacher that started using the word bookworm in a positive light? Who was this person who decided that children should embrace the term and spend their time devouring books. Metaphorically.

I have no idea.

Language usage changes. Word meanings change. In fact, the word "bookworm" had changed little from its first usages. The definition has remained pretty constant: a person or insect who devours books. We understand by context whether literally or metaphorically.

I was surprised to find in my research that there are still negative connotations. Some folks do still consider bookworm to mean someone who is so wholly devoted to books that they are unable to function in normal society.

For example, this guy:

The march of language change is still working on this definition. By the time I was hanging out in the children's department of the public library in the late 1970s, the term seemed positive. I remember there being posters and bookmarks urging children to be book worms.

And today, now that nerd culture has been more fully embraced, it seems to me that the term bookworm is more often one of esteem. Bookworms are well read. Bookworms are smart. Bookworms have the most fashionable glasses. Some celebrities identify as bookworms. I mean, Oprah's Book Club is a big deal. And I think we can all agree that Harry Potter would not have gotten through even that first year at Hogwarts without the help of renowned bookworm Hermione Granger.

So while we're all at home for a while, let's spend some time indulging our bookwormish sides.

Here's part of my current list:

And keep your books out of the basement to avoid the other kind.

March 2020

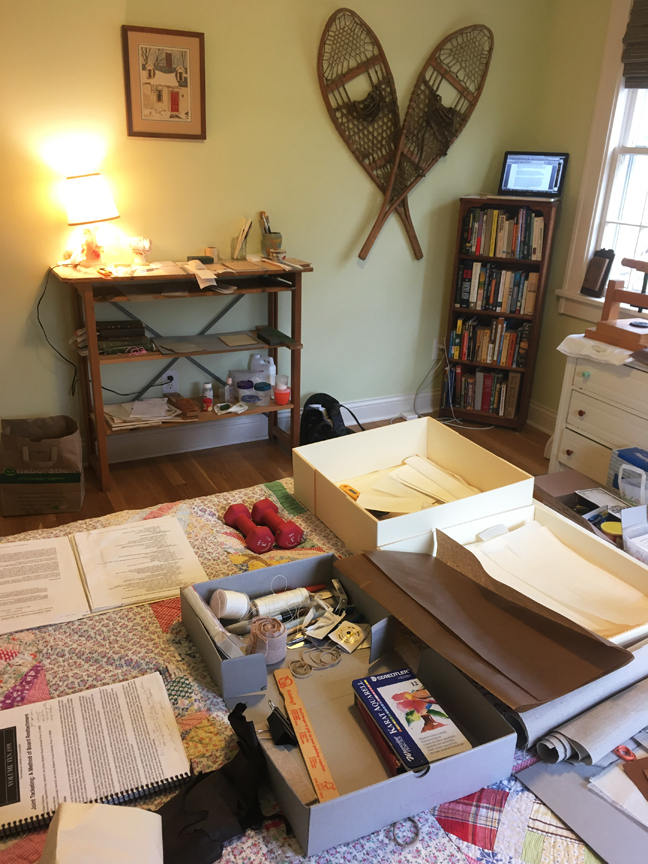

Lately I've been spending some quality time in our guest room.

In my quiet refuge, between Zoom meetings, I've been continuing work I began in a class I attended in early March on the conservation of leather bindings. In the class, led by the inimitable Jeff Peachey and held at the University of Notre Dame, we practiced the latest thing, called social distancing, as we practiced conservation treatment techniques for leather-bound books.

In my quiet refuge, between Zoom meetings, I've been continuing work I began in a class I attended in early March on the conservation of leather bindings. In the class, led by the inimitable Jeff Peachey and held at the University of Notre Dame, we practiced the latest thing, called social distancing, as we practiced conservation treatment techniques for leather-bound books.

Perhaps you noticed the snowshoes on the wall there in my guest room. Although we use them now to impart a ski lodge ambience, those are real, old-school snowshoes. My father-in-law wore them in the Vermont woods in the 1940s.

They are made from ash wood and rawhide. The rawhide is intact and unbelievably strong. Rawhide is similar to parchment, in that it is made from animal skins. But rawhide and parchment, unlike leather, are not tanned. Tanning is what makes it leather, but is also more or less where the trouble starts. Acids from tanning, plus atmospheric pollutants, lead to leather deterioration. And leather used for bookbinding is typically pared very thin, especially in the areas of stress, so that exacerbates the problem.

Hence the need to know how to repair leather bindings.

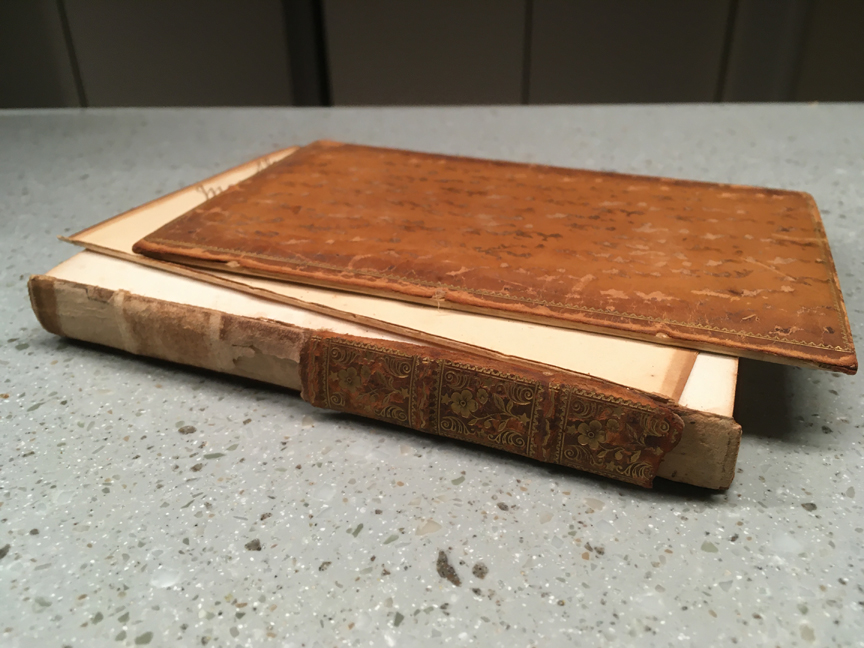

The most common way that leather bindings fail is the attachment of the cover boards to the text. The joints — the place where the covers meet the spine — are flexed every time the book is opened.

So in class we studied and practiced many ways to reattach boards, considering the pros and cons of each method, and what constitutes a good candidate for each.

Boards can be attached mechanically or adhesively with thread, cloth, paper, leather, or parchment. There are many variations and combinations among these methods, just as every book presents unique properties and problems to solve. Factors to weigh in selecting an appropriate attachment method include size; weight; condition of the paper, boards, leather, and other components; original construction; prior repairs; anticipated type and amount of use; the conservator's skill level; invasiveness of the treatment; importance of the original binding; and time (and therefore cost).

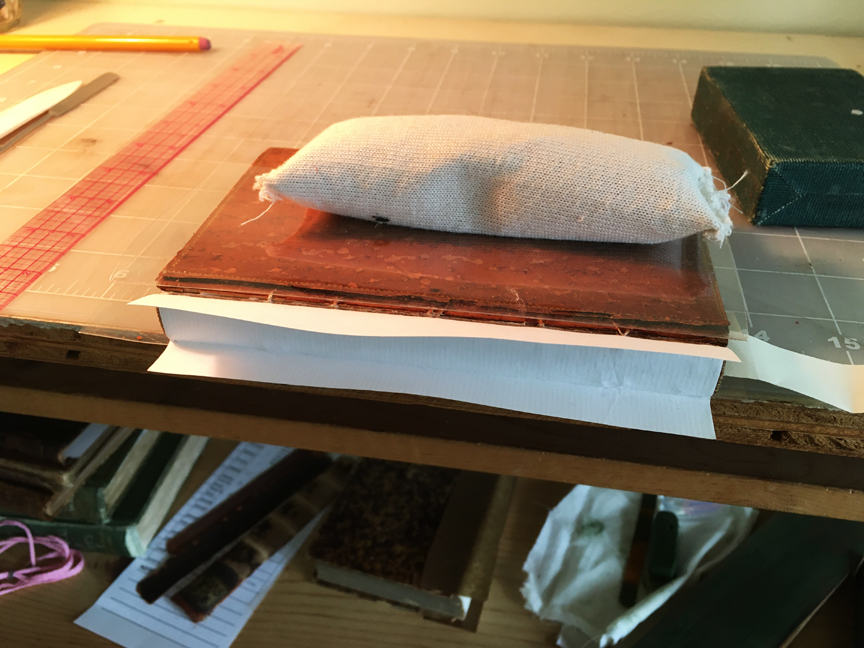

Over the first two days we discussed and practiced minimally invasive reattachment methods, including joint tackets, thread and cord extensions, board splitting, and Japanese paper hinges. These techniques are also less time consuming than traditional, shall we say old school, repairs such as rebacking or complete rebinding.

The spine of a book is also called the back, so rebacking is the replacement of a missing, damaged, or deteriorated spine with new material. Books sometimes have both detached boards and a damaged or missing spine, so they need both board reattachment and rebacking. Also, some reattachment methods involve removal of an attached spine cover to gain access to the spine of the text block.

Traditionally, rebacking was done with new leather, and was a cheaper alternative to full rebinding. Nowadays, however, other materials are often used because of concerns about leather deterioration.

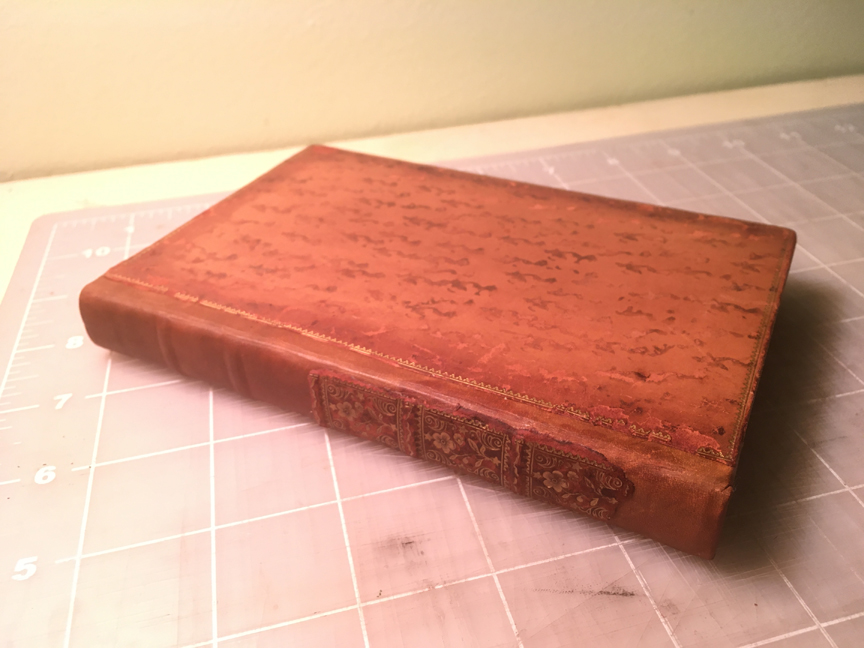

Here is a book I repaired a few months ago. Both boards were detached and the spine cover was missing. Instead of leather, I used a laminate of Japanese paper and cloth. The paper and cloth are pasted together, and the paper, which faces outside, is toned to match the leather. The cloth underneath provides additional strength.

Here the book has been rebacked with a toned paper-cloth laminate.

Here the book has been rebacked with a toned paper-cloth laminate.

But sometimes rebacking with leather is appropriate, so it is an important skill to have. So on the third through fifth days, we worked on rebacking, starting with identifying the pros and cons.

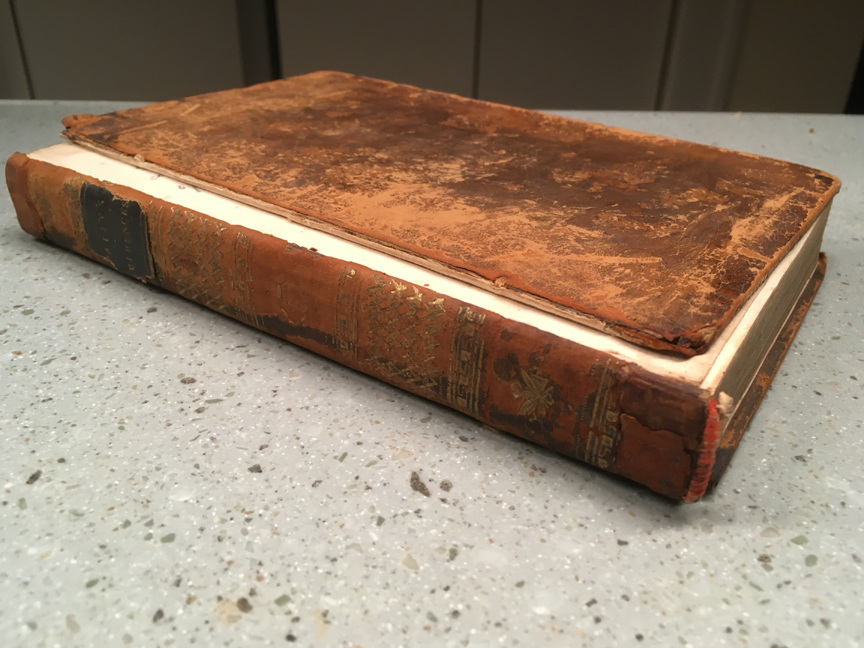

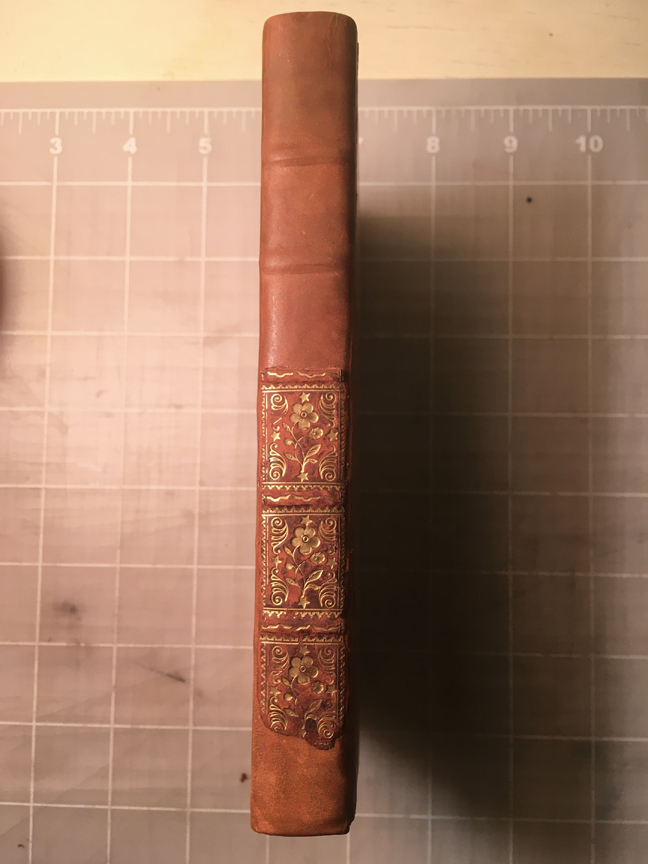

This is the little book I rebacked in leather. I started it in class, but had to finish it at home, having left a bit early the last day, times being what they are. Both boards were detached, and about half of the spine cover was missing. The thin leather has a smooth glossy surface, with the top layer flaking pretty badly in some areas. The spine covering was adhered over a hollow tube of paper attached to the book, and there are false raised bands under the spine covering.

Here a beveled cut has been made at a shallow angle along the length of the board edge, leaving a narrow strip of leather on the edge. The leather, which is thinnest at the edge of the beveled cut, is lifted off of the board from the cut line, but the narrow strip is left on. Later the new leather will fit under the lifted area and cover over the narrow strip.

Here a beveled cut has been made at a shallow angle along the length of the board edge, leaving a narrow strip of leather on the edge. The leather, which is thinnest at the edge of the beveled cut, is lifted off of the board from the cut line, but the narrow strip is left on. Later the new leather will fit under the lifted area and cover over the narrow strip.

Here the lifted leather is held up out of the way with a piece of folded mylar. The thread extensions sewn in around the original cords have been unplied (twisted to separate the three strands of the thread) and will be glued under the lifted leather, forming the attachment of the boards to the text.

Here the lifted leather is held up out of the way with a piece of folded mylar. The thread extensions sewn in around the original cords have been unplied (twisted to separate the three strands of the thread) and will be glued under the lifted leather, forming the attachment of the boards to the text.

Now the boards have been attached with the threads and a new hollow tube is being made. The middle section of the paper has been glued to the spine, then the flaps will be glued to each other. Later the new leather spine piece will be pasted out, centered over the tube, and the extended edges will be inserted under the lifted leather on the boards.

Now the boards have been attached with the threads and a new hollow tube is being made. The middle section of the paper has been glued to the spine, then the flaps will be glued to each other. Later the new leather spine piece will be pasted out, centered over the tube, and the extended edges will be inserted under the lifted leather on the boards.

We learned how to prepare new leather for use in book repair, including "boarding" to make it soft and pliable so it will shape and adhere well to the book, toning it to blend with the original leather, paring it thin in all the right places.

Here the piece of leather that will form the new spine is being pared. The first pass has been made along one long edge with a French-style paring knife.

Here the piece of leather that will form the new spine is being pared. The first pass has been made along one long edge with a French-style paring knife.

Here is the finished hollow tube with pieces of blotter glued on to create the look of raised bands. Three false bands are visible in the fragment of the original spine cover. The leather for the new spine is under the spine fragment, toned, trimmed, pared, and ready to prepare for attaching.

Here is the finished hollow tube with pieces of blotter glued on to create the look of raised bands. Three false bands are visible in the fragment of the original spine cover. The leather for the new spine is under the spine fragment, toned, trimmed, pared, and ready to prepare for attaching.

The new leather is wrapped in a damp cloth for a while, then thick paste is applied to the underside, left to sit, scraped off, pasted again, and scraped off. Then it is pasted again and put on the book. The leather darkens from the moisture, but lightens once dry. The softening helps with adhesion, shaping the leather around the bands, and getting the new leather under the lifted leather to be as flat to the boards as possible. While water is used to prepare the new leather, water on older leather is to be avoided at all costs (old leather can turn black permanently and become brittle) so the lifted areas of original leather are protected with the folded pieces of mylar.

Here the new leather has been pasted over the hollow tube and under the lifted leather on the boards.

Here the new leather has been pasted over the hollow tube and under the lifted leather on the boards.

After the new leather spine is nice and dry, the leather that was lifted from the boards is adhered down, and then pressed hard, one board at a time. The new leather compresses because it is soft and malleable, which helps everything come out smooth and flat.

After the new leather spine is nice and dry, the leather that was lifted from the boards is adhered down, and then pressed hard, one board at a time. The new leather compresses because it is soft and malleable, which helps everything come out smooth and flat.

Here the fragment from the original spine has been attached over the new spine, after removing the original hollow tube fragments from the back side.

Here the fragment from the original spine has been attached over the new spine, after removing the original hollow tube fragments from the back side.

Once the little book and I are back in the lab, I'll make a paper label for the title and place it on the spine in the panel below the top band. I hope that will be before I need the snowshoes.

Once the little book and I are back in the lab, I'll make a paper label for the title and place it on the spine in the panel below the top band. I hope that will be before I need the snowshoes.

So it's been a month. Or longer even. You've already finished all the little projects you had lying around and you've spent hours watching tutorials, webinars, and baby elephant videos. Now things are starting to get dire. Now we really have to reach deep into our bag of tricks and find some new, unusual, and possibly ridiculous projects to try out. All with the added challenge of not being able to leave the house. Well, luckily for you I tried a couple and I'm here to share my results. Now, these may not be the most practical activities, but they are fun and I imagine we could all use a little bit of that right now.

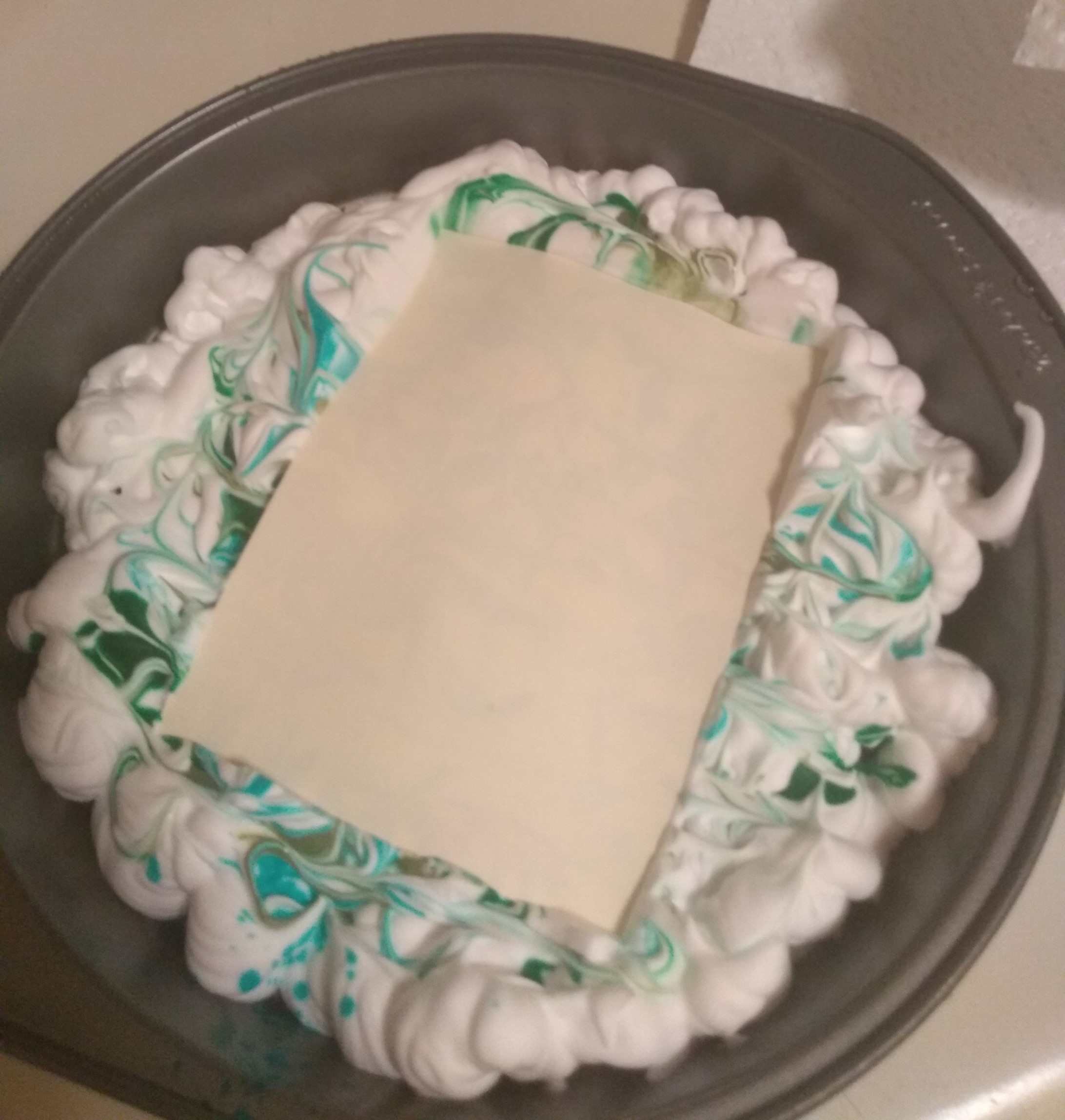

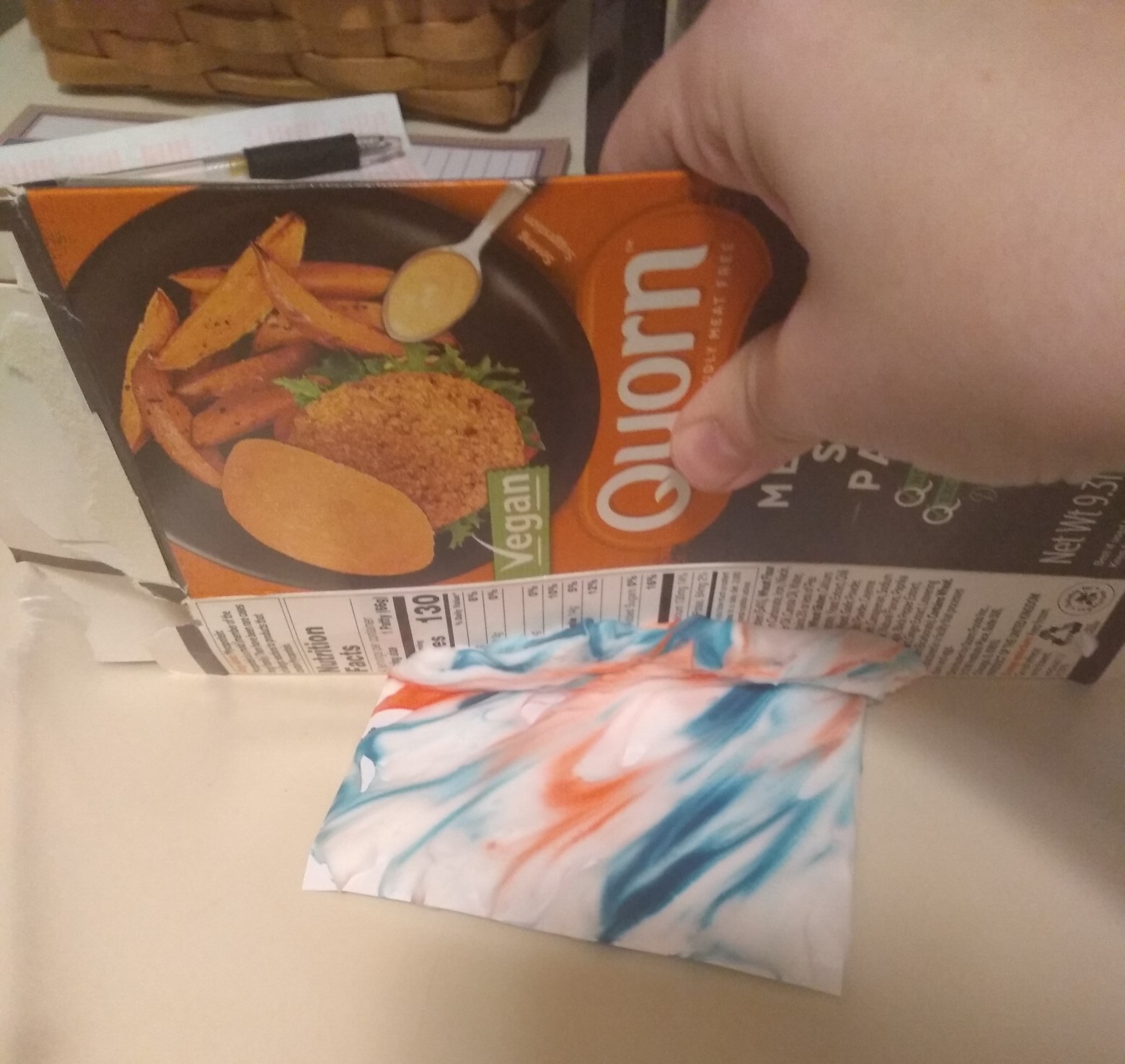

The first things I tried was paper marbling using shaving cream. This one has been on my list for awhile, because who doesn't love marbled paperandplaying with shaving cream. I think this one would be super fun to do with kids and the clean up is quick and easy.

Basically, you just spray shaving cream in a container, drop in your color, then press some paper into it.

Let the shaving cream sit on the paper for about 5 minutes, then scrape it off with a squeegee or a bit of cardboard or something.

I played around with food coloring, acrylic paint, and glitter. The resulting paper is definitely not archival, but would work well for handmade cards or something like that.

Just a note, this paper will smell like your great-uncle Carl forever and ever.

The next project I tried was making my own paper. Now, it might surprise you to learn that in my tiny apartment I possess very few of the materials that one would normally need to make paper; deckles, beaters, vats, dryers…I don't have any of those things and I imagine most of you don't either. So we'll just have to make do. We'll call it rustic! Artisanal! That makes it quaint and charming instead of a bit sad and pathetic.

The first thing you do is blend up some paper and water to make your pulp. Use whatever you have lying around! Experiment with different colors! Tear the paper up and soak it first though. It will make things a lot easier. You'll also have to use a lot more water than you think.

Then form the sheets! I used a mesh strainer because it is literally the only screen-like thing I have in my house and I'm just going to pretend I always wanted to make circular paper.

Shake the pulp around a little as it settles, but not too much. You may have to press some of the extra water out with a bit of damp paper towel.

Then, flip your paper out onto a towel to dry. The way I did this was by putting my hand underneath the sheet of paper and giving the strainer a good tap so it fell out into my hand. The paper should be solid enough that it will stay (mostly) in one piece.

Honestly, this isn't meant to be a strict tutorial and I'm sure this is slightly horrifying to actual, professional papermakers…sorry guys!

The paper will take quite a while to dry; mine took about two days, but I also wasn't able to hang it, which would speed up the process. I also didn't bother to press it. ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

So at the end of it all we're left with some perfectly serviceable, handmade paper!

Sure, it's a little wrinkly, but it's paper! I think it would be quite nice for gift tags or other little decorative objects.

So, there's two easy and fun projects for everyone out there to try! And both have endless possibilities for improvement (really…just endless…) and experimentation! Good luck out there and stay safe!

I assume that you, dear reader, have recently found yourself spending far more time than you are used to (or would like to) at home. Well, I've got good news for you! The first bit is that you are keeping everyone around you safe by spending more time indoors, and we thank you for that. The second bit, is that I have some tips and suggestions for how to keep the fires of your preservation passion alive while stuck at home.

The first tip is an easy one, one which you're already doing. Blogs! We have lots of great posts here on this site, why not take a look at our backlog? Then when you're done with that, check out a few of my own favorites.

Duke University's preservation blog

A beautiful blog by artist Hannah Brown with lots of embroidered leather bindings

Preservation at the National Archives

Preservation at the Parks Library at Iowa State University

Once you're properly inspired and energized, take this opportunity to check in on your own collections. Are all of your books and papers stored safely?Are any of them sitting on the floor, in front of a furnace, under an old, leaky AC unit? If so, pick them up! Then have a look at this post or this one to learn more about safe handling and storage. Take steps now to ensure that Grandma's old copy ofThe Joys of Jello is available for future generations to enjoy!

A quick and easy way to keep your books in tip-top shape is to make sure you're using them gently and correctly. I realize it's unreasonable to think that anyone could refrain entirelyfrom eating while reading, and I will be the first to admit to occasionally finding myself at the end of a book with an inexplicably empty family-size bag of Cheetos next to me, but we can at least take sensible precautions. Make sure your hands are clean when handling books and don't leave them anywhere where food or drink could be spilled on them.

And while we're on the subject of food, don't use it as a bookmark! A few years ago the Guardian had a very interesting article about the wide range of disgusting items found in books, and we can relate! Our very own Elise Calvi once found an entire slice of moldy tomato!

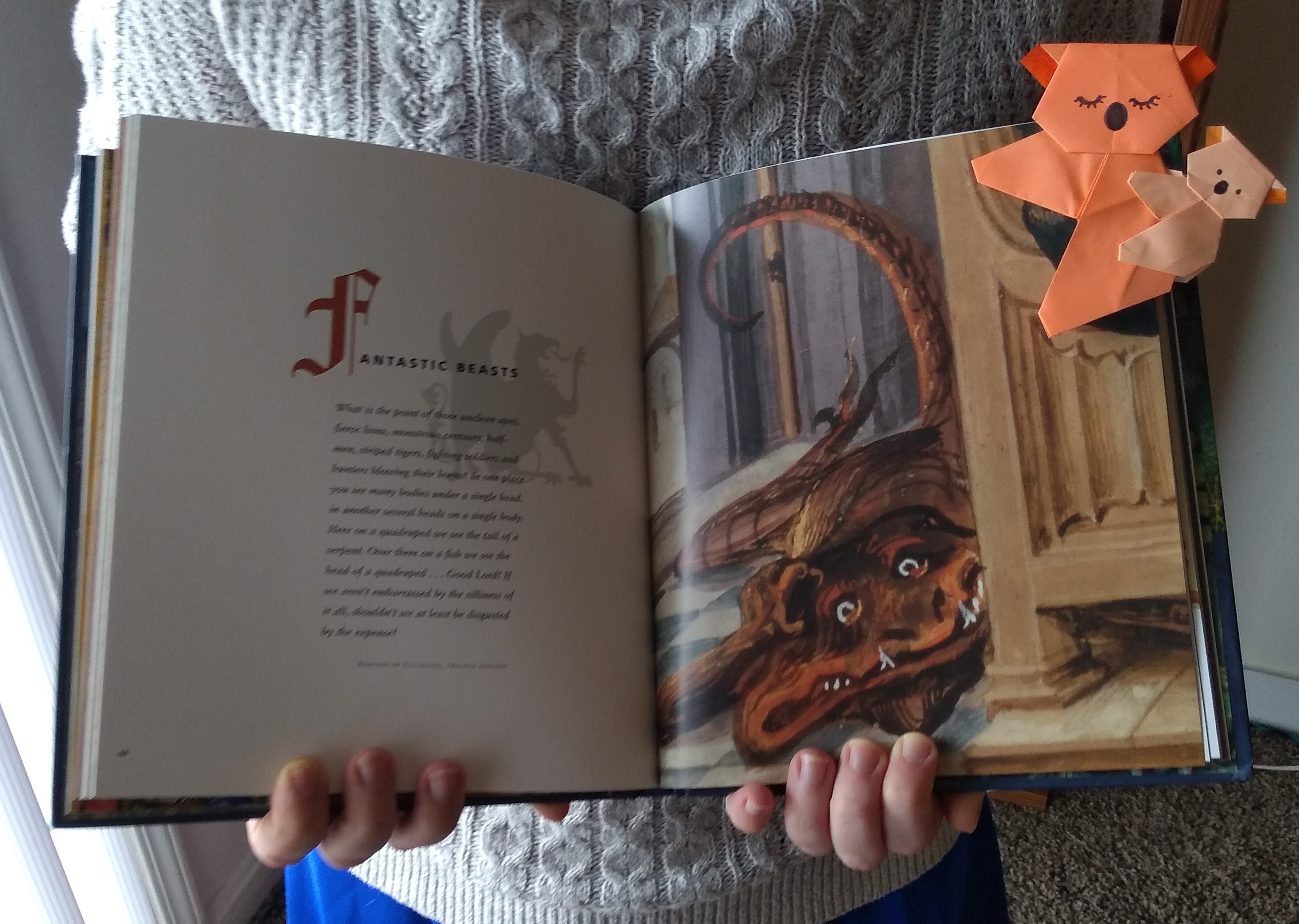

Why not make some bookmarks instead? They will keep your books in perfect shape and they're so cute you'll never forget them and be forced to use produce in a pinch. Here are some of my favorites.

A cute cat!

An adorable koala family!

An elegant crane!

A…dragon? Kind of?

And since you've already fallen in to this YouTube rabbit hole, why not make yourself a whole miniature library! There are so many things you can do with tiny books! Make necklaces, earrings, keychains! The world is your oyster!

I hope this gives you a bit of inspiration for how to spend your days at home. Stay tuned for more suggestions! Stay safe out there everyone!

I spent a very enjoyable day last week over at the University of Illinois' Urbana-Champaign campus presenting a lecture and then conducting a series of hands-on workshops upon the invitation of Jennifer Teper, Velde Professor and Head, Preservation Services. The topic of the day was the "Technology of Writing". Over the course of an hour I explored the various writing implements and traditions of several cultures- European, Islamic, Far Eastern and Mayan civilizations.

The morning talk was attended by primarily Conservation and Preservation staff, though a few select members of the public were also invited. Afterwards this eager group of fifteen jumped into learning how to cut quill pens and exploring writing with various inks (including the walnut ink we made in-house this past August) and writing instruments (quills, reed pens, writing brushes, steel nibs).

The afternoon event was an open house at their Rare Book & Manuscript Library. The library was currently displaying an exhibit curated by the Conservation Department entitled "The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly: Conservation Treatments and Decision Making Through the Ages". Cookies, cakes and coffee created a festive atmosphere; adding to this, tools and materials for quill cutting and writing were set up. In no time at all, dozens of students and staff arrived wanting to try their hands at cutting goose feathers to create a writing instrument used from roughly the 6th century up until the mid 19th. By the end of the afternoon, the door count was 132! By all accounts, it was a successful event and I'm proud to have played a part in so many people visiting the library- hopefully there were some new visitors who will keep coming back.

When I had some free time between the day's events, I was generously hosted and given a tour of the Conservation Department by members of staff. It's always a pleasure to talk with other conservators- we invariably share methods and learn from each other. The University of Illinois is in the Big Ten Academic Alliance, as we are here at IU. Library collection size and scope and organizational structures are similar; so they encounter similar challenges within their conservation and preservation departments as us. This made for a good heart-to-heart discussion.

The lab is currently developing some in-house papers utilizing agricultural waste in conjunction with Fresh Press. I spoke a bit with staff members Quinn Ferris and Anneka Vetter about the testing- both physical and chemical- of these papers in order to create a product that satisfies archival needs. The topic brought me back to many years ago when I worked in a laboratory ageing and testing for clues to paper deterioration.

Also of interest to me were the innovative enclosure and display solutions the Exhibit Conservator, Marco Valladares Perez, has come up with in order to reduce the amount of material purchased (and often thrown away afterwards).

The day ended with a staff holiday pizza party at RBML with Library Head, Lynne Thomas, and her staff.

Looking back, I've always found that these sort of hands-on materials talks and workshops generate a lot of interest and enthusiasm. Though much of what is covered is no longer in widespread use in the 21st century, people are always eager to learn about the past and have a hand at new skills development.

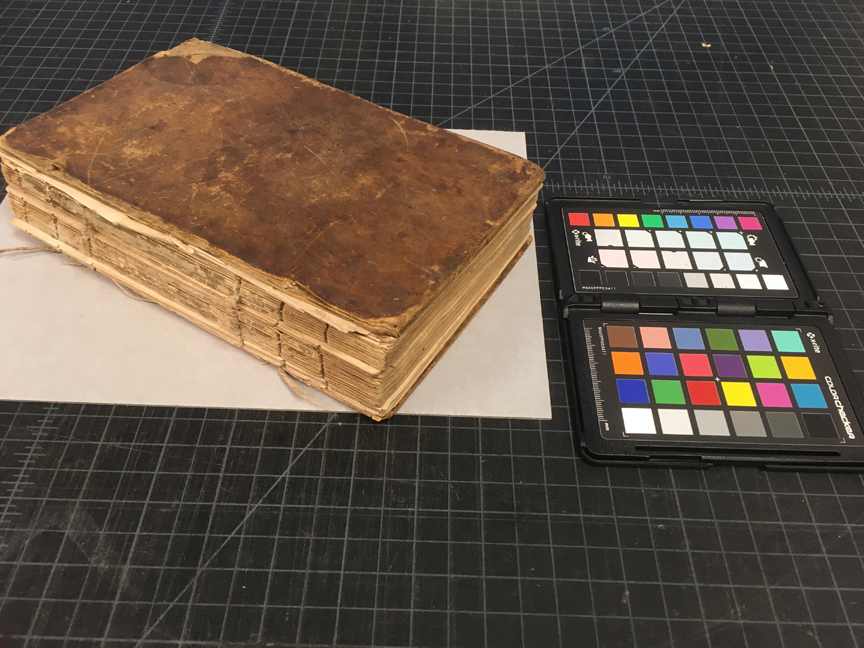

On this blog, we often post about new techniques that we are learning in order to take better care of our collections. We are always trying to continue our education and ensure that we are able to take the very best care of the items entrusted to us. But sometimes the new techniques we learn aren't actually "new" at all, as was the case this past September.

In mid-September, we participated in a three-day workshop on historic bookbinding materials and structures taught by Atlanta-based conservator, bookbinder, and owner of Big River Bindery, Andrew Huot. Andrew taught us nine of the most common European methods of bookbinding in use from the eighth to the nineteenth century, as well as four methods of board attachment, how to make a laced case binding, and even generously included an impromptu headband sewing session! It was a busy few days, for sure! Understanding how books are made helps us "unmake" them, so we can repair them. It is probably unsurprising to hear that the print collections at many libraries are circulating less as focus shifts to electronic subscriptions and online information. Less circulation for the print collection means we spend less time fixing the everyday sort of damage books normally incur. Although we still work on many new items, we are finding that we now have more time to spend assessing the older portions of the collection, so we were very happy to have the opportunity to enrich our knowledge of pre-19th century bookbinding.

Books for the Preservation of Knowledge of Humanity

Source: https://blogs.libraries.indiana.edu/craiglab/